Upon being inaugurated as the 35th President of the United States (US) on Friday, January 20, 1961, John Fitzgerald Kennedy widely known as JFK made a famous challenge to the Americans “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

More than six decades after JFK speech, the phrase still reverberates with timeless urgency. JFK’s words echo even far beyond the boundaries of America down to the Global South in Botswana, where a small nation is undergoing a metamorphosis as characterised by a shift in the political climate, economic outlook, and social fabric which are all being tested by waves of apathy and disillusionment, making the JFK message to feel tailor-made for our times.

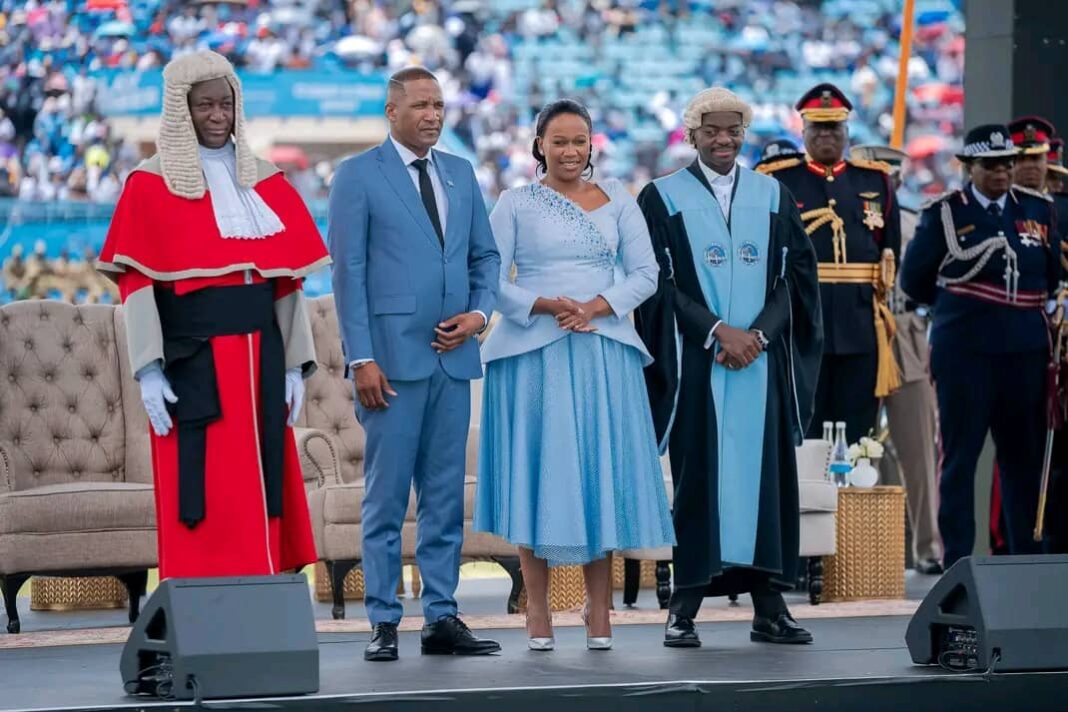

This period of transition was ushered in November 2024 when the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC) defeated the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), signalling a change of government after its 58 years in power. In that period, Botswana went from rags to riches and now is back at rags again.

Nevertheless, now the country is not building entirely from scratch. But there is more to be done in restoring it to its former glory. Otherwise, all is still not lost for the Sub-Sharan nation that seeks to grow into a higher income economy by 2036.

Once celebrated as Africa’s shining example of democracy and good governance, Botswana now stands at a crossroads. We remain politically stable and economically sound by many global standards, yet beneath this stability lies a quiet erosion of the civic spirit that once defined us. Botswana’s story was built on sacrifice, service, and shared vision, but over time, we have drifted towards dependency, entitlement, and complacency.

If Botswana is to reclaim its moral centre and secure its future prosperity, citizens must reawaken to a fundamental truth: nation-building is not the responsibility of government alone, but a collective responsibility as seen during independence. It is a collective endeavour. Every Motswana must begin to ask, not what the country can do for them, but what they can do for their country.

In the years following independence in 1966, Botswana was a land of scarcity and simplicity. With just a few kilometres of tarred roads and a modest budget, the young republic had little more than hope, unity, and a visionary leadership. Sir Seretse Khama and his contemporaries understood that the country’s survival depended on civic duty and collective effort. Citizens were encouraged to build schools and clinics with their own hands through initiatives like Ipelegeng and self-help projects. The “Motho le Motho Kgomo” or “One Man, One Beast” campaign as spearheaded by our national forebears when Botswana established its own public university, the University of Botswana (UB) in 1982 bears testimony to this self-reliance.

That was a period where a generation took pride in doing something for the country. They saw service as honour, not burden. Development was viewed not as a favour from government, but as a shared national project.

Fast forward to today, and the contrast is striking.

Many Batswana have become passive recipients rather than active participants in the nation’s progress. We have become accustomed to waiting for government jobs, waiting for tenders, waiting for subsidies, waiting for solutions, and the least is endless.

However, while it is important to fully emphasise the need for state driven economic intervention especially considering the model of our economy, the honours is on every citizen to deeply reflect wherever they are that in the event their county falls short or under goes a period of transition amidst the face of adversity as is the case, what role do they have to play. What is the role of civil society, the church, traditional leaders, law makers, politicians, elderly, young people, the media, business community and generally community at large in such a time? Do we stand and fold our hands whilst magnifying the challenges or embark on a collective endeavour to address them for the betterment of our people? That is the question.

In his passionate inaugural address, apart from JFK calling for all Americans to unite in combating their challenges, he urged the global community to equally do the same.

“My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Finally, whether you are citizens of America or citizens of the world, ask of us here the same high standards of strength and sacrifice which we ask of you. With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help, but knowing that here on earth God’s work must truly be our own,” he said.

Over time, the spirit of self-reliance, unity, cooperation and all that which formed the cornerstone of Botswana’s existence as a new republic has now being consumed by this “waiting culture” which has quietly stifled initiative and productivity. It is now common to hear people complain that “government must do something” about unemployment, waste management, or community development — yet very few ask what they can do to improve their own surroundings.

The shift from contribution to consumption has left Botswana vulnerable. Our sense of shared responsibility has weakened, and the concept of citizenship has been reduced to service delivery expectations.

Consequently, we have become a nation of spectators in our own democracy. Election after election, voter turnout continues to decline. Public participation in community meetings is sparse. Volunteerism, which was once a mark of civic pride has been replaced by demands for allowances and incentives. Even in public debates, the loudest voices often belong to critics who offer little in terms of solutions. Social media has given rise to a generation of “keyboard activists” quick to complain but slow to contribute.

Criticism, though necessary in any democracy, becomes hollow when not paired with civic engagement.

Worth noting is that democracy, after all, is not a spectator sport. It demands participation. It thrives when citizens play an active role in voting, volunteering, mentoring, innovating, and holding leaders accountable through informed dialogue.

The question is not whether Botswana’s government is doing enough. The question is whether Batswana themselves are doing enough for their country.

No conversation about Botswana’s future can ignore its youth as they are the largest demographic group, and arguably the most restless. For many young Batswana, the country feels like a promise unfulfilled. Unemployment remains stubbornly high, opportunities seem few, and frustration is widespread. Yet, amid this despair lies immense potential. Botswana’s youth are educated, connected, and globally aware. They possess the creativity and energy needed to drive innovation and social change. What is missing is a shift in mindset from expectation to contribution.

Young people must begin to see themselves not merely as victims of economic stagnation, but as catalysts for transformation. If opportunities are scarce, then innovation must take their place.

There are already signs of this new spirit: young entrepreneurs turning local problems into business ideas, farmers introducing technology into agriculture, artists using their platforms to challenge social norms, and digital creators reshaping Botswana’s identity online. These examples show that doing something for one’s country doesn’t always require political power or vast resources but begins with initiative. For instance, a young person who plants trees in their village, mentors school children, or creates a small local enterprise is contributing just as meaningfully to national development as any government programme.

Further, at the heart of this conversation lies Botho, the moral and philosophical foundation of Batswana society. Botho teaches that our humanity is intertwined with that of others, that respect, responsibility, and compassion are not optional virtues but essential elements of a functioning society. When Botho thrives, communities thrive. When it fades, corruption, selfishness, and moral decay fill the void.

Sadly, Botswana’s moral compass has been tested in recent years. Scandals involving corruption, abuse of power, and declining work ethic have become all too common. These are not merely political issues; they are moral ones. They signal a deeper cultural drift -a weakening of the Botho that once defined us. Reclaiming Botho means more than teaching it in schools or reciting it in speeches. It means living it in how we treat others, how we conduct business, and how we serve the nation. It means understanding that patriotism is not about self-enrichment, but self-sacrifice.

A society driven by Botho does not wait for the government to clean the streets; it organizes clean-up campaigns. It does not complain about youth unemployment; it supports young entrepreneurs. It does not tolerate corruption; it exposes and rejects it.

Too often, patriotism in Botswana is expressed through symbols like waving flags, wearing traditional attire on Independence Day, or singing the national anthem with pride. These acts are important, but they are not sufficient. Real patriotism is measured by action, not ceremony. It is seen when a public servant refuses a bribe, when a business owner pays fair wages, when a teacher stays after hours to help struggling students, or when citizens hold leaders accountable through lawful and informed means.

Patriotism is not blind loyalty; it is constructive commitment. It is about caring enough to challenge what is wrong and contribute to what is right.

For too long, we have mistaken patriotism for passive celebration. But Botswana’s next chapter requires active citizenship, one grounded in values, guided by ethics, and driven by purpose.

Moreover, its undoubtable, that leadership matters.

Citizens cannot be expected to give endlessly if leaders are not seen to do the same. The moral authority of government derives not from its power but from its example. When leaders serve with humility, integrity, and transparency, they inspire citizens to do the same. But when leadership is tainted by self-interest or greed, cynicism takes root.

Thus, Botswana’s leadership, whether political, business, traditional, and religious must therefore rekindle the ethos of servant leadership. They must remind citizens that public office is a duty, not a privilege. That leadership means stewardship, not self-service.

However, this does not absolve citizens of responsibility. A mature democracy thrives on mutual accountability.

Leaders must lead, but citizens must also engage, question, and participate. Civic responsibility is not the government’s burden alone; it is a national pact.

Economic patriotism is another crucial frontier. Botswana’s dependency on imports and limited industrial base are not just structural problems. They are reflections of our collective attitude toward production and consumption.

To ask what we can do for our country is also to ask: What can we produce for it?

Every local purchase, every locally manufactured product, every business idea that creates jobs instead of exporting capital is an act of patriotism. Supporting local industries from small farmers to fashion designers strengthens the national economy and reduces vulnerability to global shocks.

Moreover, Botswana’s push toward diversification will succeed only if citizens participate as creators, not just consumers. The government can design policies and provide incentives, but it cannot innovate, farm, or build on behalf of the people. Economic growth must be people-driven to be sustainable.

Basically, Botswana’s development has always been a shared journey. The partnership between citizens and government-built schools, hospitals, and roads that transformed a once impoverished nation into a middle-income country. But the next stage of development one that demands innovation, competitiveness, and moral renewal cannot be achieved through government effort alone.

The state can enable; it cannot inspire. That task belongs to the people.

When citizens take responsibility for their environment, their education, their communities, and their moral choices, the country becomes stronger. Shared responsibility breeds shared prosperity. As a result, the notion that “someone else” must fix the country is both unrealistic and self-defeating. There is no “someone else.” There is only us, the people of Botswana, with our diverse skills, passions, and capacities.

In truth, this is not just a political or economic argument; it is a moral one. It is about rediscovering what it means to be a Motswana, a person of Botho, service, and dignity.

When we choose to serve, we honour those who built this nation from nothing. When we contribute, we strengthen the bonds that hold us together. When we act with integrity, we safeguard the future for those who will come after us.

Botswana does not need more spectators; it needs builders. It needs citizens who see service as a calling, not a cost. It needs leaders who lead by example, and communities that uplift rather than divide.

Let us, therefore, reawaken the spirit that once made Botswana the envy of Africa-a spirit of unity, hard work, humility, and moral strength.

As we look toward the next 60 years of Botswana’s journey, let us internalise Kennedy’s immortal challenge and give it a local heartbeat:

“Ask not what Botswana can do for you, but what you can do for Botswana.”

That means asking ourselves daily how can I make my workplace better? How can I uplift my community? How can I inspire integrity and Botho in those around me?

Botswana’s destiny is not written in diamonds, policies, or speeches. It is written in the actions of its people. As they say, the true wealth of a nation lies not beneath the ground, but within the character of its citizens.

So, let us be a generation that gives more than it takes, that builds more than it breaks, and that believes in the quiet power of contribution.

Only then will Botswana not just survive but thrive not because of what government did for us, but because of what we did for our country.